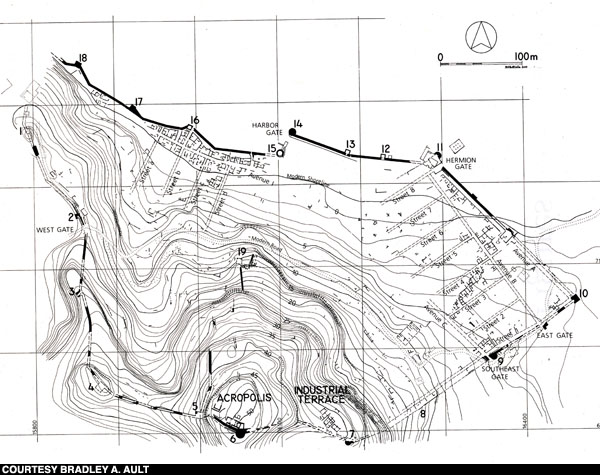

the plan of Halieis' site

with the remains and

excavated areas

source:

Accessed : 01 November

2010

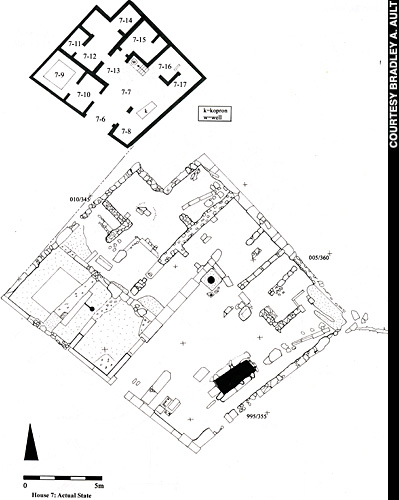

plan of House 7

source:

Accessed : 01 November

2010

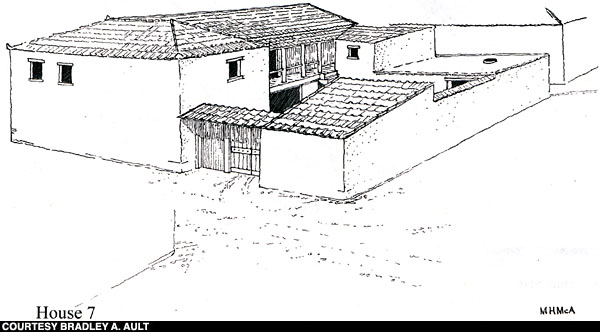

reconstruction of House 7

source:

Accessed : 01 November

2010

|

“In reality every polis is in a natural state of war with every other, not indeed proclaimed by heralds, but everlasting; and if you look closely, you will find that this was the intention of the Cretan legislator; all institutions, private as well as public, were arranged by him with a view to war.” (Plato, Leg. 626a-b)

The organization of the Greek city was usually based on the legislation created for it. But the fact that war was a premise taken into consideration everywhere in Greece can be evidenced by the fortification. The wellknown Danish archeologist P. Flensted-Jensen underlines this: “[..] I would still be inclined to argue that a substantial circuit wall was the sine qua non of the Greek polis.”1 The fortification wall, indispensable tool for every polis, was also an important characteristic of Halieis, a town in Argolida, in the south of the Peloponnese. While the region seems to have been inhabited almost 50.000 years ago, in the area of Halieis the earliest findings date from 3000 BCE. According to Herodotus, its residents were the Tirynthians, who in 465 BCE were routed out of their city by the Greeks of Argos. After that the Hermiones seized the large village which took its name from the main occupation of the new inhabitants (Halieis – Alieis (Greek: αλιείς)= fishermen).

As mentioned above, part of the city of Halieis preexisted although there are only few architectural elements that do not belong to the Classical era, with the fortification of the early Acropolis being the main one. The city walls had firstly been constructed during the 7th century BCE, but due to wars and occupations, they were rebuilt and expanded many times, resulting in a total length of almost 2 kilometers which included nineteen towers and five major gates. The urban enclosure of approximately 18ha, due to its geomorphology, is divided into an Upper and Lower town.

The Lower town comprises the regular plan of Halieis city and is an important example of town planning of the Classical period. It is estimated that the area was inhabited by approximately 2.500 people in 450 to 500 houses. It was abutting on the fortification of the port which was determined by two towers with a circular plan, whilst the opening between them could be barred with a beam.

With part of the Lower Town and the port being submerged due to sea level rise, the excavations have so far revealed three areas with housing districts in the eastern part of the city and three housing blocks further north. Close to the Southeast Gate (numbered 9 in the excavation plan) a single residence was completely recovered, which is known as House 7. Housing in ancient Greece is the most important element providing evidence for the social organization. With most of the Classical and Hellenistic cities following a regular plan while having different legislation influencing their daily life and mentality, the closed housing space is the space to be analyzed cause this is where the main differences become visible . As mentioned also at the database entry of Olynthos, isonomia (equality under the law) was the reason for isometria, a type of standardization in planning, by “extending the idea of equality to house parcels and field systems, gardens and burial plots”.2

Most of the experts have been trying to group the housing plans in Classical Greece in specific categories for better understanding. The prostas type (Piraeus typical house plan), the pastas type (Olynthos' housing) are just some of the categories that have been enriched with the hearth-room houses, the peristyle ones, etc. The pastas and the prostas refer to the porch and the difference lies in that the prostas gave access to only one room whereas pastas to a series of rooms. In Halieis, this porch exists in one or the other form, whereas the main element associated with the entrace was the prothyron.

The architectural element of prothyron refers to a lowered doorway which ensured a sheltered hall and it is found in nearly all the houses excavated at Halieis. House 7, which

provides extensive information, was built on a plot of 231 square meters. As a typical example of vernacular architecture, natural stone was the main material used for the construction, with unmortared ashlars [stone work] along the frontage and mud-mortared ones for the inside and rear walls. The structure of the pitched roof was based on a timber framework and was covered with terracotta pan and tiles. However, the traces of staircases that imply the existence of a second floor (for some houses), would mean that probably part of the roof might have been flat.

The prothyron (which literally means: pro (προ) + thyra (θύρα) = before the door) was connected to a courtyard which comprised 23% of the house area and had a multi - functional character. This courtyard was found at the southern part of the house, so that “the sun’s rays penetrate into the pastades in winter, but in summer the path of the sun is right over our heads and above the roof, so that there is shade”.3 By reading the floor plan of House 7, one can observe that there is no real continuity between the rooms, but they are rather segmented, deployed around the courtyard. At the northern part of the yard, there was the andron and its anteroom. The andron and the gynaikon were two rooms referring to men and women accordingly and were found in the majority of the ancient Greek houses. However they differed in use and importance. In Halieis, the almost square andron of 21,5 m2 provided space for seven couches (klines), while the off-center door indicated a specific amount of privacy.

On the one hand, the andron could be the proof of women - men distinction, but its importance lied in that it represented the koina(common public functions) in the domestic sphere. The transit of the gathering of people for political discussion outside the public space of the city, to the domestic one, was the representation of democracy within the realm of the house. It seems that these sympotic (commin together) moments were the only ones when the andron in Halieis' houses was used mainly by men. It is very interesting to note this fluidity in the boundaries between private and public space in terms of the function. While the house represented the private space within the city and the prothyron marked this transition, the public space with the agora made their appearance in the andron. In the end, the anteroom was just the “intermediate space between the domestic and sympotic realms”.4

As in Olynthos, even? in Halieis, there is evidence of a domestic economy based on food and textile production. However in Halieis the small shops along the streets have probably not been an important organizational principle. According to the classicist M.H. Jameson, "On a small scale, the private house shows the democratization of aristocratic values, which was in so many ways characteristic of the city-state.".5 Nevertheless, the fact that Halieis had its own coinage along with the size and the importance of the (now submerged) port of the city indicate that after the domestic economy another economy was developed mainly based on trading and fishing.

While Plato mentioned that the legislation of the ancient Greek cities was based on the premise of war, it is evident that even the planning and organization followed the same presumption. Cities were usually developed in areas chosen for their prominent or strategic position. The city of Halieis was recognized? for the hidden port and the strategic position of the acropolis and this is the reason for which it was occupied by the Athenians and the Spartans during the Peloponnesian war (431 BCE – 404 BCE). However, this was not the reason for its historical end; the city was abandoned for uncertain reasons after 300 BCE and was never reoccupied.

Footnotes:

1. Flensted-Jensen P., Hansen M. H., Nielsen T. H., Rubinstein L.,(2000), Polis and Politics: Studies in Ancient Greek history, Museum Tusculanum, Aarhus, Denmark

2. Bradley A. Ault, Living in the Classical Polis: The Greek House as Microcosm, The Classical World, Vol. 93, No. 5, The Organization of Space in Antiquity (May -Jun., 2000), pp. 483-496. Online available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4352441 (accessed: 01/11/2010 )

3. Xenophon, Memorabilia 3.8.9 – 10

4. Bradley A. Ault, Living in the Classical Polis: The Greek House as Microcosm, The Classical World, Vol. 93, No. 5, The Organization of Space in Antiquity (May -Jun., 2000), pp. 483-496. Online available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4352441 (accessed: 01/11/2010 )

5. M. H. Jameson, "Private Space and the Greek City," in Murray and Price (0. Murray and S. Price, eds., The Greek City from Homer to Alexander (Oxford 1990) ) 171 - 195

source: 1. Bradley A. Ault (2005), "The excavations at Ancient Halieis : The organization and use of domestic space", Bloomington, USA : Indiana University Press.

2. Marian H. McAllister (2005), “The excavations at Ancient Halieis : The fortifications and adjacent structures”, Bloomington, USA : Indiana University Press.

3. Dig Greece - Ancient Halieis (2008), the Archaeological Institute of America

and the Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (USA), [online]. Accessed : 01 November 2010.

4. A brief History of Ancient Halieis, Comcast Interactive Media (2007), [online]. Accessed : 01 November 2010.

5. Wikipedia. Vocbulary entry : Πορτοχέλι Αργολίδας. Accessed : 01 November 2010

6. Wikipedia. Vocabulary entry : Αλιείς (αρχαία πόλη). Accessed : 01 November 2010

7. Argyri Xanthi, “The harbour of ancient Halieis”, [online]. Accessed : 01 November 2010.

8. Flensted-Jensen P., Hansen M. H., Nielsen T. H., Rubinstein L.,(2000), Polis and Politics: Studies in Ancient Greek history, Museum Tusculanum, Aarhus, Denmark

9. Bradley A. Ault, Living in the Classical Polis: The Greek House as Microcosm, The Classical World, Vol. 93, No. 5, The Organization of Space in Antiquity (May -Jun., 2000), pp. 483-496. Online available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4352441 (accessed: 01 November 2010 )

10. M. H. Jameson, "Private Space and the Greek City," in Murray and Price (0. Murray and S. Price, eds., The Greek City from Homer to Alexander (Oxford 1990) ) 171 - 195 |